To this day, the concept of rural Jewish life is characterised by the notion of Jews as traders, and particularly throughout the villages in the Hunsrück as cattle traders. Over centuries, majority Christian society had forbidden Jews from acquiring land and from gaining membership in the craft or merchants’ guilds. An actual "choice of professions" was not possible under these circumstances, which is why Jews living out in the countryside had to search for other options to make a living. These options were limited to trade, which was quite often associated with small loans made to farmers in the remote rural villages. It wasn’t until the French era („Liberty, Equality, Fraternity“) around 1800 and the subsequent Prussian era after 1815 that changes in their marginalised societal situation slowly began to take hold.

Jews in the cattle trade

Small land holdings and livestock trading became the main sources of income for Jewish families; a situation that changed only slightly until after the First World War. The Hunsrück was a cattle rich region due to its favourable topographic features. The numerous market towns in the 20th Century were enhanced by the first railway connections from the Nahe River via Simmern, Kastellaun and Emmelshausen to Boppard with interconnections via Kirchberg, Hermeskeil and Trier, as well as a branch line to Gemünden. Many Jews settled where railway lines facilitated the transport of goods and livestock. The Middle Rhine section between Koblenz and Bingen was opened in 1859, which ultimately led to seven of the nine cattle and horse traders in Boppard after 1926 being Jewish.

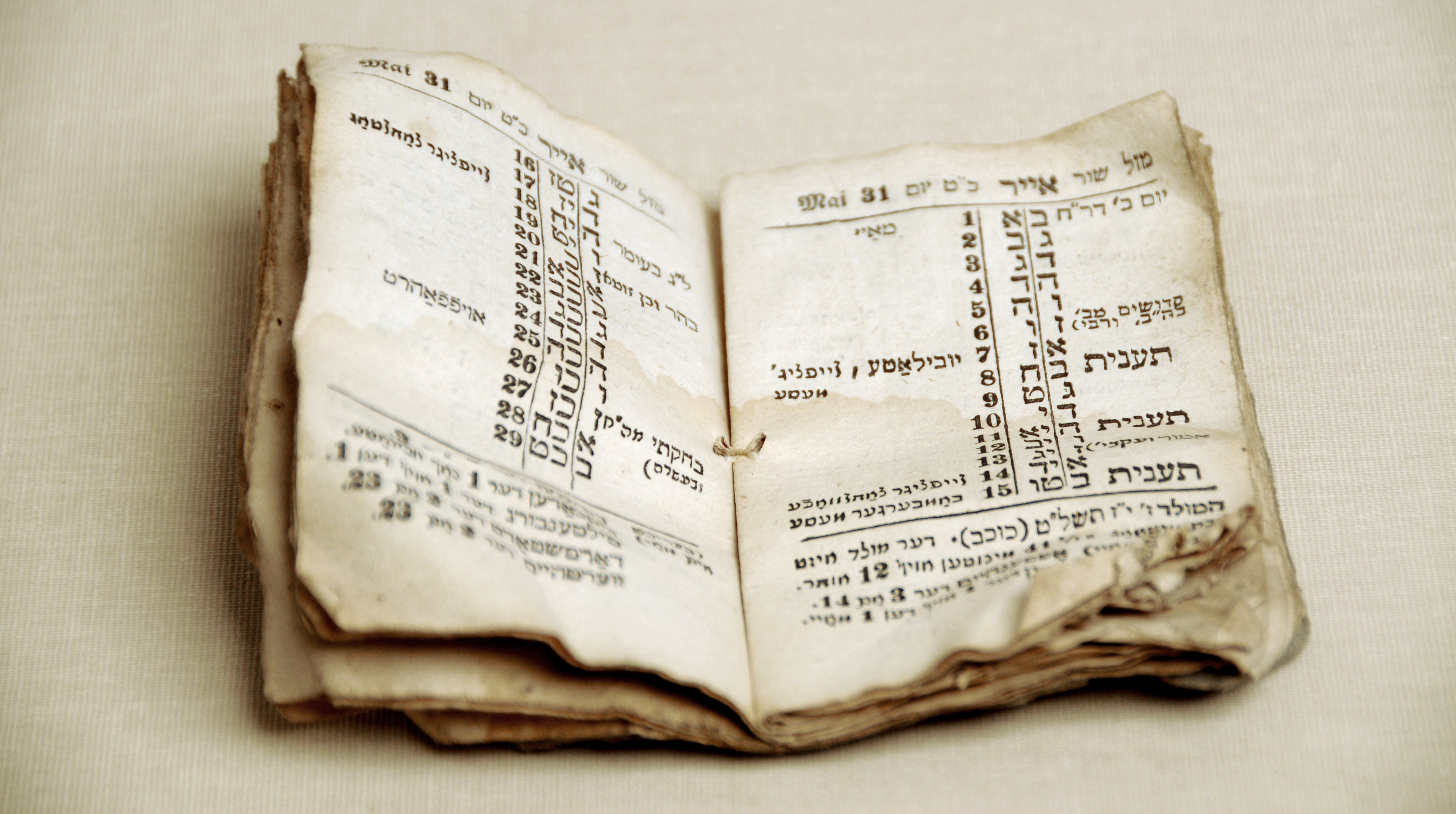

Moreover, it was the religious ritual of shehitah (kosher slaughtering) that kept the rural Jewish population closely bound to the livestock trade. Only kosher animals that had been slaughtered according to Biblical commandments and prohibitions were permitted for consumption. For this reason, the cattle trade and the shehitah had to be taken into their own hands - resulting in the slaughtering, the trading and the selling evolving into a closely knit unit.

Livestock trading, however, was very vulnerable to potential crises (epidemics, harvest failures, etc.), which is why Jewish families increasingly strove to afford their children better educations and different professions.

„My father was determined to provide us a proper education and to prepare us for sound professional careers. Any respectable craft would have been preferred over livestock trading...“

Up to the Second World War, reports from the various district administrators indicate that the Jewish livestock traders were indispensable for the Rhine-Hunsrück region. Once the progressive exclusions began in 1933, the cattle drives to the largest livestock market in Kastellaun declined so significantly that farmers began complaining about the lack of trading options.

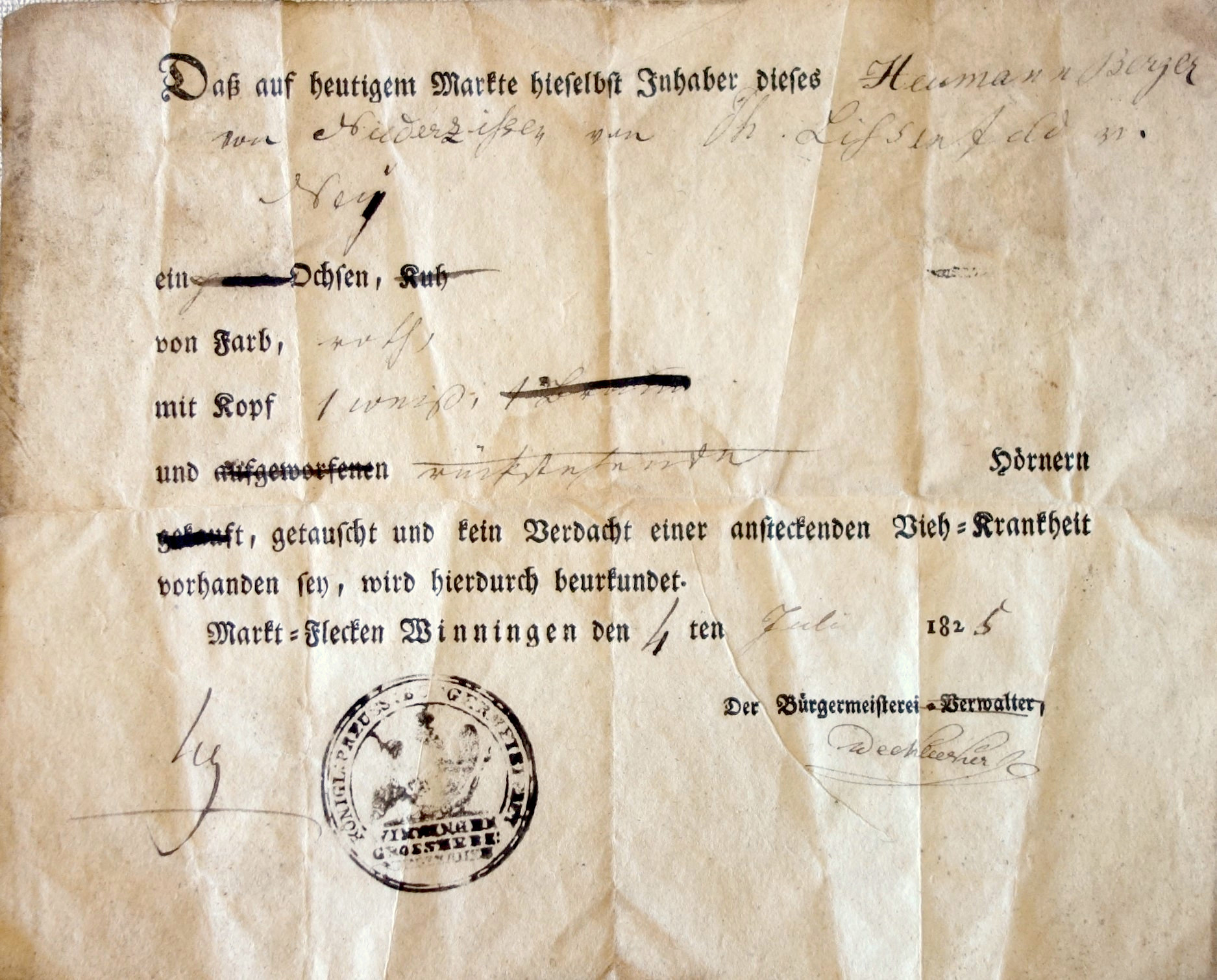

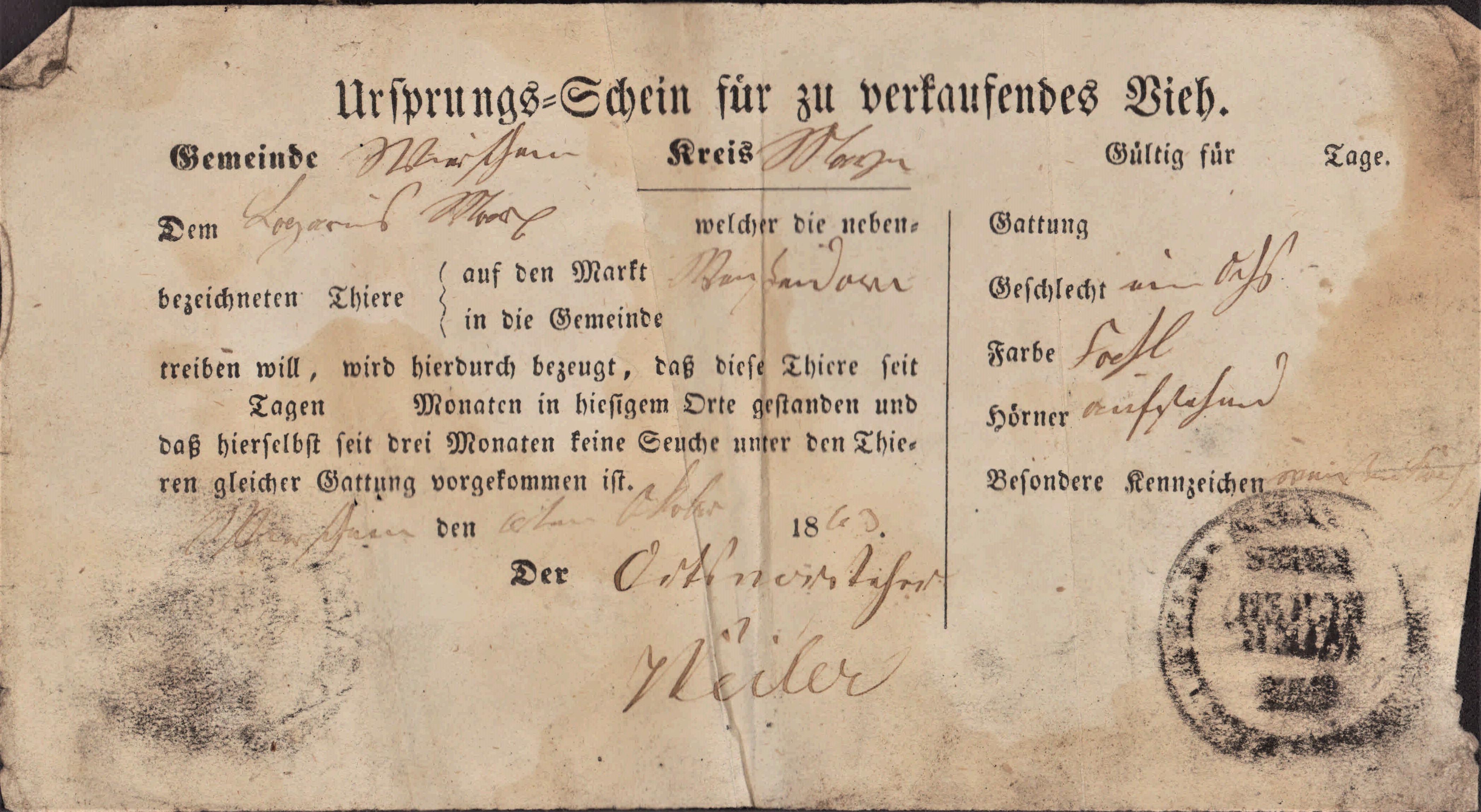

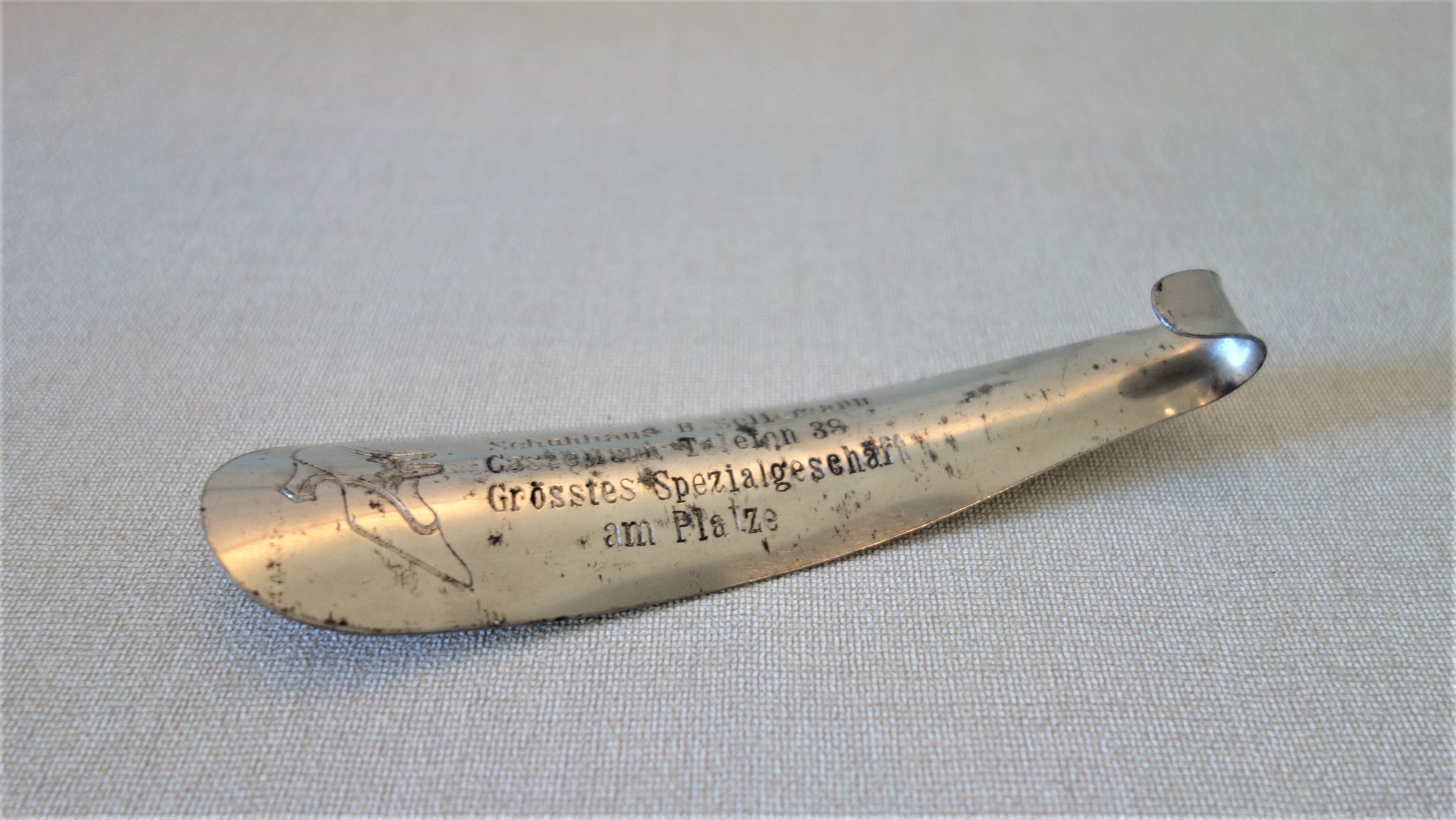

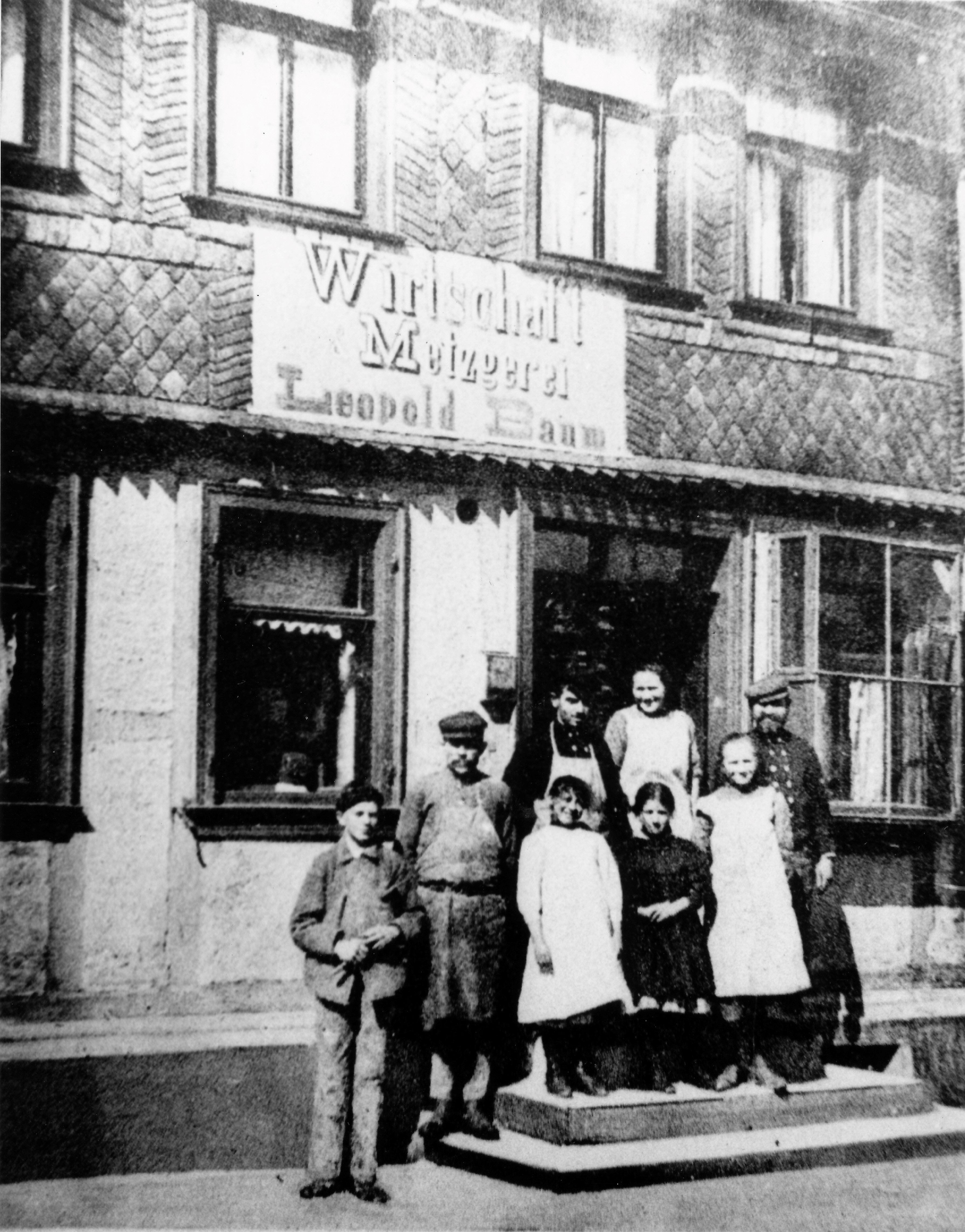

The following photographs and objects convey an impression of the livestock trader’s work and the relationships established between the Jewish and Christian trading partners.

Crafts and other trade professions

Farming activities were also closely tied to the economic activities in other sectors. Jewish traders frequently acted as intermediaries between the rural and the urban areas: They sold farm products at regional and interregional markets while bringing products in return from the cities to the rural population. These included kosher products for their fellow-believers, as well as manufactured goods, linen and cloth fabrics, bedding materials, furniture, military supplies (after 1914), colonial goods, tobacco, oils and fats. They initially marketed their merchandise as peddlers and itinerant merchants, commonly travelling long distances on foot, carrying their wares packed in baskets on their backs. It wasn't until the 19th Century that the gradual transition to being merchants with fixed retail shops had run its course. The merchant profession is invariably characterized by a high degree of mobility with an extensive network of business contacts. As such, they imported not only goods from the cities, but urban fashions, interests and ideas, as well. Monika Richarz depicted the Jews as a "bourgeois element in their countryside villages” for this reason.

Jews had also become more active in the skilled trades in the wake of increasing social integration and equality in the 19th Century. They especially dedicated themselves to those professions important for practising religious rituals. Aside from the butchers’ trade (kosher butcher or shohet), these included such professions as baker, dyer and textile processor. Academic professions, however, remained the exception.

Even prior to 1933, this concentration of just a few professions provided anti-Semites a welcome excuse for depicting Jews as „blood sucking“ mongers whose only objective was to defraud and exploit their Christian trading partners. As can be seen from the occupational distribution, the spread from the wealthy merchant to the peddler and day labourer in the Rhine-Hunsrück region was enormously wide, with no indication that a general state of prosperity existed. A large portion of the Jewish population in the 19th Century lived under the same impoverished conditions as their non-Jewish neighbours.

The following slide presentation shows just a few of local businesses and shops, and only hints at the ultimate fate of the families affiliated with them.